|

|

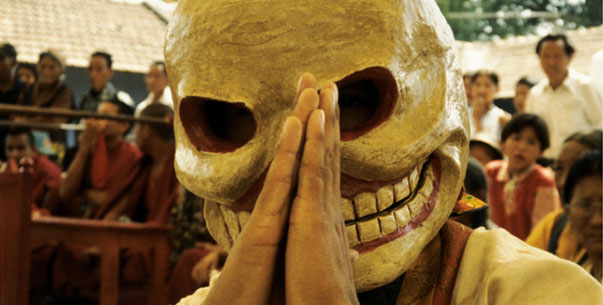

scared sacred

Documentary filmmaker, Velcrow Ripper made a conscious decision to travel to some of the world’s most dangerous places. What did he find there? He found hope.

by hardeep dhaliwal

video still by velcrow ripper, scaredsacred.org

In a five-year journey resembling a rite of passage, filmmaker Velcrow Ripper went to thirty ground zeroes in search of hope and filmed his process. Several of the places he visited are featured in the film Scared Sacred.

“I set out due to a sense of impending doom,” says Velcrow Ripper about his five-year odyssey to the world’s darkest places, beginning in 1999. “The millennium was not yet the great letdown it turned out to be,” says Ripper. “Even though I didn’t believe in the Christian view of the apocalypse I was becoming increasingly aware of darkness and dark days ahead.

“I did the opposite of survivalists who were digging holes, stocking up on food and water. My approach was to head straight into the darkness and the darkest places in history. I went out to face my fear. We all focus on the light where there is clarity, illumination and knowing, but darkness is the flip side where there is not knowing and potential.”

His sojourn included travels to Bhopal, Cambodia, Hiroshima, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Israel, Palestine and also New York City where he happened to be on September 11, 2001. He also participated in intensive spiritual retreats with Sufis, Greek Orthodox monks, Tibetan, Thai and Zen Buddhists, as well as an Interfaith group in Israel.

The first place we see in Scared Sacred is Bhopal, India, where eight thousand people died overnight in 1984 due to a leak at the Union Carbide chemical plant and where thousands more die every year from related diseases. “I arrived right after three months in an intensive Buddhist meditation retreat in south India. Imagine going from that into a toxic wasteland. I was overwhelmed, but then began to meet people and witness their awe-inspiring strength.

“The strongest people were those who were able to take action,” says Ripper, describing one man he met who recounted the story of women survivors who broke into the Union Carbide factory in an incredible moment of collective action, all the while singing and chanting. They felt a sense of power and for the first time since the tragedy no one was crying.

A Cambodian man tells the story of how his parents were killed by the Khmer Rouge and he was then forced into the KM and trained to lay landmines in the killing fields. Since the war ended he has worked tirelessly, using only a wooden stick to decommission between fifty and one hundred landmines every day.

In Afghanistan we meet a young woman from the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA). Her mother was a member of RAWA and killed by the Taliban. Raised in the RAWA orphanage, she has gone on to become a RAWA member herself. In a country where it is against the law to educate girls, she risks her life to show Ripper the work she does in a school for girls.

“Activism becomes a source of strength,” says Ripper. “Spirituality and activism go together. Taking action is not just marching in the streets. In Bosnia I met two artists who during the four-year siege of Sarajevo created art by collecting the debris of war and transforming it into sculptures. The only freedom they had was in their minds. This is what allowed them to survive.”

In Hiroshima, Ripper found this poem by survivor Tamka Hari:

Lost in the shifting sand, in the midst of a crumbling world, the vision of one flower.

“The film is not looking to make bad things into good, but for that single flower that is able to grow through the debris and rise to the sun,” he says. “In every place I found it in some way.

“The biggest challenge was in Israel and Palestine,” he continues. “I wasn’t sure I’d find hope there. I was shot at twice and then they threw a concussion grenade.” In a clip from Scared Sacred, Ripper appears shaken, stunned but otherwise unharmed after this incident.

\ “I had a phantom sensation of a bullet entering my back,” says Ripper. “Then there was this sense of release and laughter. It’s a funny moment, but it’s a sad moment because you can see how vulnerable I am. While I ran from the walled barrier being erected by Israel, I asked myself, ‘What if my child was shot? Would I want to strap a bomb to my body and take revenge?

“Almost in answer to this question I met a group called the Bereaved Family Circle. They are both Israelis and Palestinians whose children have been killed in the conflict. One of their projects is called ‘Hello Peace,’ where any Palestinian or Israeli can phone 611 and be connected to the enemy just to talk. They’ve had 300,000 calls in three years.”

Throughout his time at the ground zeroes, Ripper maintained his sense of humour. His shoes were stolen in many of the places he traveled. “At the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment, I go to meditate under the Bodhi tree, come back and my shoes are gone.” His camera, car and other possessions were stolen at regular intervals during his travels. He interprets this experience as practice in letting go of material goods. It helps him focus on his métier.

“I’m an explorer. That’s my job description,” says Ripper. His parents are Bahai and he grew up learning about all the world religions.

\ “Independent investigation of truth is a key tenet of the Bahai faith and this has guided my documentary films even though I left the faith at sixteen to find things out for myself.

“My purpose as a communicator is to gather stories and pass them on. It is a responsibility. In Hiroshima for ten years people were not allowed to tell their stories and they were treated like lepers. This silencing is called re-victimization. It prevents healing.”

Everywhere he went he used the Tibetan Buddhist visualization practice of Tonglen meditation. “I would have been overwhelmed without it. In Tonglen you breathe in suffering, transform it, and release it as compassion. It helps me stay open to what is there without becoming numb or paralyzed with hopelessness. In New York City I was doing Tonglen and realized I was breathing in particles of the dead. So the practice becomes literal.”

In New York he spoke with Sensei Enkyo (Pat O’Hara), director of the Zen Peacemakers Order located just a few blocks from Ground Zero. She says, “If ordinary human beings in the world can see their own suffering and can really feel their own vulnerability, then perhaps they can become aware of the vulnerability and suffering of others. That’s what going to a sacred place, going to a place where great suffering has taken place, is about. It’s opening yourself completely, and acknowledging it, and not blocking it. That’s the transformative moment, when you begin to see that you’re not separate from any of the people involved, perpetrators and victims. And then change can hap- pen. That’s why people need to go to Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, they need to go to Cambodia. And now, here.”

Ripper describes how he has changed since embarking on his sojourn: “I’m a completely different person. I feel a real sense of strength, increased sensitivity and openness without being a feather in the wind. I’m not in a fixed place and don’t want to be. I’ve made a leap. I’m left with this ability to see each face as my own. My sense of boundary and isolation has lifted.

“I have a sense of excitement about humanity. I’ve gone to the darkest places and am left with a sense of inspiration and vulnerability,” says Ripper.

Ripper quotes Cornell West, a Prince- ton professor, theologian and author: “Optimism and hope are different. Optimism tends to be based on the notion that there’s enough evidence to say, ‘Looks pretty good out there, things gonna be better.’ Much more rational, deeply secular. Whereas hope looks at the evidence and says, ‘It don’t look good at all.’ But we gonna make the leap of faith, go beyond the evidence, to create new possibilities based on visions that become contagious to allow people to engage in heroic action, always against the odds, no guarantee whatsoever, that’s hope. I’m a prisoner of hope. I’m gonna die a prisoner of hope. Never gonna believe that misery and despair gonna have the last word.”

Does hope live only at ground zero? Ripper believes hope is everywhere; it’s just harder to find when swamped in material things. “I have a relentless sense of hope, it is really indestructible. All the survivors I spoke with say they have hope. Without it, people can’t go on. It’s an inspiring force. A Buddhist Hungarian astrologer told me this is the era of the thousand Buddhas. There will be many awakened souls, not just one saviour. Humanity itself is the saviour. How often do you get a chance to be born at a time like this?”

Velcrow Ripper is the writer, director, narrator, cinematographer and editor of Scared Sacred. He is a Genie award-winning filmmaker, writer, web artist and sound designer. He has directed over 30 films and videos, both fiction and issue-oriented documentary, often with an experimental edge. Hardeep Dhaliwal is a regular contributor to ascent magazine.

|