|

|

living in poesis/

a day with pier giorgio di cicco

(an interview with my interrupting yet thoughtful interjections)

by clea mcdougall

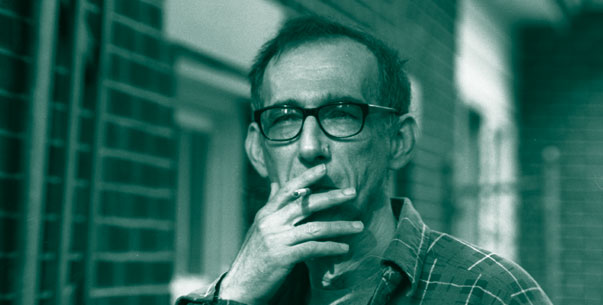

photo by sarah e. truman

introduction/suspicions of poetry and god: okay letís go

White petals are falling.

Our wineglasses slowly drain. Sarah and I talk about God, our day in Ontario, Father Di Cicco. Sarah says, There are probably lots of geniuses hiding out in the woods, doing mass.

I say, I hope so.

Before I met Father Di Cicco I had been carrying around a napkin with his name scribbled on it for over a year. Pier Giorgio Di Cicco. That name was tucked away in my purse, in the terrible handwriting of a friend who had told me about a poet he used to know, a poet who stopped writing when he became a priest, but recently began to publish poetry again.

This interested me immediately.

Poetry and God. Two things I am slightly suspicious of, but tend to spend most of my time thinking about. Itís not very often that those two things come together in an acceptable way, but I respected my friendís opinion very much, so I went to find this Di Ciccoís books. When I found them, I didnít know quite what to do.

We all look for what speaks to us Ė poems, novels, songs Ė our experience reflected back, but more eloquently than we could have put it. So seldom is it that I see my own experience on the page, and not only my own present experience, but how I imagine my past and future to be.

Yet there it was.

Funny that I find myself in a car with Sarah driving out of Toronto on our way to meet Di Cicco. I somehow knew I would meet him the moment I opened up one of his books, but as we turn off the highway, onto country roads, I wonder what exactly I am doing here.

The other day my friend who scribbled Di Ciccoís name down emailed me, saying, In his most recent phase Di Cicco acts as priest: outsider as holy mediator, and as a poet:†the outsider as the betrayer of brotherhood. But in doing so he also marks the very conditions of community, the finite singularity of beings divided from themselves. Put in other words, as poet/priest he is the gatekeeper to ďcommunion.Ē

And I thought, yes, yes! Beings divided from themselves. I am divided from myself! So, am I searching out the poet/priest to receive this communion? Maybe, maybe not, but I do feel that I will find some answers; Iím just not sure what the questions are yet.

Di Cicco lives in the Ontario countryside, north of Toronto. We get out of the car and try to find our way through the mess of country living to his door. He finds us first, squints at us through his cataracts, and after a kiss on each cheek, inquires about the colour of our eyes. He shows us around his land, gestures out to the soft hills, and says, this is the honeymoon wilderness.

The Honeymoon Wilderness is also the title of his first book of new poetry after fifteen years. Maybe I have never spent much time with a poet, one whose work I know really well, but the day unfolds like this Ė at every turn are fragments of his poems, in his speech, on his wall, the dripping faucet, cactuses, the fruit-picking ladder made out of one log that reaches up to nowhere. He leans against it and I say, you wrote a poem about that ladder. Itís the first time all day that I call him on it, and he looks at me with a particular expression of mistrust and astonishment; maybe he was surprised that I actually read his poems, I donít know.

The land is wild and untended. His house is spare and accented with í50s furniture, some kitschy Catholic knick-knacks, a few books (ranging from vintage fiction digests to Derrida for Beginners), old records, and not much else. On the wall is a painting of Route 66, complete with blinking red lights. Heís a mix of backwoods hermit, high-talking philosopher, man of God and Canadian poet. He gives weekly mass, teaches at the university and has recently been made the poet laureate of Toronto. His priestís collar lies on the kitchen table alongside ashtrays and coffee cups. This is where we spend most of the day.

we begin/what the f*** is metaphysics?: a lesson

But at first we sit in his living room. Iím glad Sarah has come along, because she is occupying Di Cicco with grandiose arguments of dualism. For the time being, I get to sit back and observe. Very quickly I know what we are in for. Poet Dennis Lee has described Di Cicco as ďgregarious, intelligent, cantankerous, lonely, droll, obsessive, impulsively tender.Ē And I would have to agree with him.

Di Cicco begins like this, and it is typical of how the day follows:

I hate to jump on the old bandwagon, but the bad guys still appear to be the Greek philosophers. But what is it that presupposes a people to become dualistic? We tend to look for psychological, philosophical, social, anthropological answers to this, and this is very easy for us to do, because we are a very non-somatic society. We donít think in terms of the body in North America or Nordic countries, and the answers may be in the intelligence of the body and not in the body of the intelligence.

The metaphysics of any people are predicated by land and the environment that they are from. What is it in ecology that predicates thinking, feeling and reasoning? As central a thing as light. As light. The light in the Mediterranean is very dramatic. It goes from sky to earth. Thereís a movement you can see and feel, a movement; itís like the light of heaven shining on the Earth. Youíve got two things already that predispose you against a metaphysic of one joining with the other.

Sarah leaves to load the camera and poke around the grounds. I try getting background material on Di Ciccoís life, but he acts bored, and isnít having any of it. I canít tell if he is avoiding answering my questions, or just doesnít like the subject matter. He wants to engage, and he doesnít want me to be the interviewer. At one point our conversation goes like this:

How has being Italian affected your poetry?

What do you mean? Why do you ask that?

I donít know, it was your segue. You started talking about poetry, then said how Italian you are. Are they connected?

Iím still trying to figure that out. It would look like the attempt to reconcile oppositions like Italian and American, Med and North American would seek to find its resolution through the arts, but I donít think so.

Iíve realized lately that we tend to explain much of what we do by socio-cultural-anthropological backgrounds. But in fact, we are propelled by a metaphysic. And that metaphysic gives birth to the cultural, not vice versa. Culture has become God in the 20th and 21st century. We think everything is explained by culture. I donít believe that to be the case. As I was mentioning earlier, just as the light predicated philosophy, metaphysics predicates the culture.

The way Italians make an arc of a gesture with their hand, thatís simply a gestural mimetic, of the relationship between what is around the body and the body. Our bodily expressions are expressions of our relationship to the land. Our thoughts, our syntax, are predications of that, our cultural habits are predicated by that. So that my poetry was a result of a certain kind of metaphysic. Ö

Let me take a rest. Let me think. Itís not wise to think rapidly. When you think rapidly, you are forced to syntax, to narratives, to scripts that may not be genuine. Thatís why the poet takes time writing. So as not to fall into predictable and handed scripts. I trust myself in poems; I donít trust myself in conversation.

Thatís interesting, because you like conversation.

Yeah, I especially like it because it can become a poem. Thatís the best part of conversation. Mostly it doesnít; mostly itís dialogic. And poetry is not dialogic.

What is it?

The poem is always about becoming one. The poem creates oneness in itself and draws the reader into oneness. It seeks to become. It seeks to become the reader. The dialogic doesnít seek to become, the dialogic likes separateness. Itís a difference between the unitive and the binaristic.

My metaphysic has always been impelled to the unitive. I suggest that all metaphysics, all people are impelled to the unitive, but by apparently different strategies.

And your strategy has been poetry and prayer.

Yes, poetry and prayer Ö I need a glass of orange juice. Do you want more Pepsi?

No, I still have some.

a bit of background/why he became a priest: making eggs

I do manage to squeeze a few biographical details out of him. Pier Giorgio Di Cicco was born in Arezzo, Toscana, Italy, in 1949. His family moved to Montrťal when he was three, but he grew up mostly in Baltimore and considers himself of the particular Italian American breed. He moved back to Canada in the late 1960s to attend the University of Toronto and live among the thriving Italian-speaking community.

He published his first book of poetry in 1975, We Are the Light Turning, and went on to publish over a dozen books until he moved to a monastery in 1983. After four years he decided to become a priest and for the last seven years has been ďa country priest, which in some way duplicates the best aspect of hermitage.Ē

Di Ciccoís exit from the literary community in the í80s was abrupt and unexpected. ďArtĒ and ďReligionĒ are two institutions that, when entered into at a very serious level, are often exclusive of one another. The boundaries are not usually transcended, and yet Di Cicco has made this movement seem fluid and effortless. And it also seems as if he just doesnít give a shit what people think. He prays, he writes. ďWhat difference does it make if you write on paper or on your heart?Ē he asks me.

Maybe we could talk about the time in your life when you decided to become a monk. Iím curious about the time leading up to that, how you made that decision and what impelled you toward that life.

Well, I had done most things that anyone would want to do, at the age of thirty-three.

Yes, but what attracted you to prayer?

I had gone through an intellectual conversion. I had just finished a book called Virgin Science, which was a poetic restructuring of holistic paradigms that were available, and psychology and physics, quantum mechanics, holographic theories of consciousness, you name it. Back in the í80s when these things were beginning to be popularized; now they are sort of household ideas. I thought I would take that route, looking for a scientific apologia for spiritualityÖ butÖ

Why donít you turn that off and let me have a couple of eggs. Iím a little peckish.

I lean against the kitchen counter, trying to look at ease, a false grace I affect when I am nervous but want to seem as if I know what I am doing. The act of turning off the recorder loosens him up and breaks apart the awkward relationship of interviewer and interviewee.

What I really want to know from him is how and why he became a priest. I want to know for this article, but also as a person who has had thoughts of ďreligious vocation,Ē I want to know what it takes, what happens in a life, so that the decision can be made, the step taken.

But how did you start to pray, why did you go to the monastery, what was your life like then, the circumstance that made this happen, how did you make the decision? This is something I need to know. You were my age then Ö

And between the melting butter, the empty eggshells, he tells me. He was my age then.

I sneak the recorder back on. The sound of eggs frying.

And were you bored with yourself?

Yeah! I need to be excited, I needed an intellectual conversation, I needed to be inspired. I needed to be Ö fulminated, epiphanied. Looking back on it now, who else but God could excite? Who else understood physics and poetry, or whatever, the most esoteric; who else was I going to go to? The Internet? Like everyone is doing now?

Thatís why prayer came in. Prayer. You see, I could talk to God about anything and he would listen. I needed to hear him. I didnít hear God for a long time because I was mentalizing him. You know how I did that? By not talking to him.

Vocal prayer is essential. If we are body, and you canít leap from the somatic condition in prayer, then you have to pray through the body; that means talking to God the way I am talking to you now. Excuse me! (he shouts at me) Iím talking to you! Iím not thinking about you. I mean youíre real, body, voice, touch. Hello! People say, Oh, well, God is an abstraction. Well, heís an abstraction if you treat Him like an abstraction! God speaks through the self-revelations of the somatic, kinesthetic. And the body is kinesthetic, because when you talk with the body, the mind and heart come together. When kinesthesis is reached, then Godís presence is manifest. Hence people feel the presence of God at parties Ė why? Because they are somatic with the incarnational components of each other. The rest of the time they go home.

In yoga, the holy trinity is body-mind-speech Ö

Yes, exactly. The phonocentric is essential in prayer. People come to ask me how to pray. I say, have you tried just kneeling in your apartment and looking up and talking to God, you know what I mean? We donít want to look ridiculous to ourselves, do we? And sometimes thatís all it takes. Youíre going to feel ridiculous to yourself if you say to someone you havenít known for long, but you feel like youíre in love with (grabs my arm), I think I love you. Because you donít know! You might get slapped back, rejected. Well, God is no different than a lover. You know? He loves you but, Iím sorry, he wants you to come out and say, I think Iím in love with you! These are such basic things!

We are called to talk, to unite. We are called to recognize and be recognized. We are called to recognize the indistinguishable, the inextinguishable, the appetite, hunger Ė thatís the metaphysic. We are all called to the unitive, but some are called with particular passion. It sounds elitist, but some are called with particular passion. As near as I can tell, there simply are more passionate people and less passionate people. It doesnít mean that the less passionate people arenít all walking toward the unitive. But some have to run.

broken hearts/living in poesis: we have coffee

It is near the end of the afternoon. We are all sitting at the kitchen table. The way he talks about a unitive metaphysic sounds to me like the idea we have in yoga of liberation or enlightenment, or moving (maybe running) toward something we think could be freedom. So I ask him,

How do you understand liberation?

We have this idea that we want to be free. (laughs) We donít understand that being free means saying goodbye to things that we are not ready to part with yet and donít want to part with and some things that we will never be ready to part with. You know, there is this gung-ho wholesale run toward the embrace of total freedom. The price of that is ominous; the cost of that is ominous. Not in terms of what we pleasantly call risks. The freeing of yourself may involve the loss of yourself. Thatís a nice idea, because we have this idea of self as this ego, as this barking little dog, that once we get rid of it, the house will be tidy again. But I mean self, who you are, recognizable to yourself by any demonstrable means. Thatís a scarier proposition. Not just throwing out the dog, but the furniture as well.

You know, the dark night of the soul is more than just a psychological overhaul. A lot of us think it is. I want to be free on my own terms; I want to be holy on my own terms. Being holy, I donít know much about it, but it seems to me that itís about having your heart broken so many times that you donít have a heart anymore. You donít have a heart anymore.

Well, you have heart, but itís a useless paradigm, ícause hearts are meant to be mended. What if theyíre meant to be broken and have water run through them like the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon? I mean, everyone wants a heart that can be mended. But what if we are not called to a mended heart? Scary. I for one am not ready to surrender the metaphor of a heart that can be mended. Iím fifty-four years old; Iím still not ready.

Let me make you some coffee. Turn that thing off.

Sarah and I sit in silence for a while, contemplating the possibility of a heart that is not meant to be mended. Di Cicco conducts the day with these odd and stunning metaphors. It is at once exciting and exhausting. I think, where am I? Here we are, at a very regular Formica kitchen table, in a rather empty kitchen, at an ordinary house in the country. But he keeps saying things likeÖ

Ö this is as palpable as the flesh, as the style of love and the texture of someoneís benevolence. What do you think of that? It sounds ratherÖ.

Poetic.

Poetic, eh? I did three public lectures at the university this year, slamming Aristotle. I had everyone believing that they were in poesis. As soon as the lecture was over they slipped back down the slippery slope of dualization, of thinking that thinking and feeling were two different things. The whole point of being a good metaphysician is that you can have a thinking feeling and feeling thought. Thatís the binarism to stitch back together right there. If you can do that, you can do anything.

Itís not as if intelligence is outside the heart; itís not as if mind is without feeling. But how do we manage to be that way? Language goes a long way to defeating us. What perpetuates the dualism, is language. It perpetuates linear thinking. Thatís why poetry is good for nonlinear thinking. Syntax is within Newtonian time, past, present and future. Poetry, which I claim is where we mainly live, whether we admit it or not, is in the timeless.

Have some cream.

sadness/we arrive at the end of our day: sarah takes a picture

Itís starting to make sense to me now. I described reading his poetry at the beginning, as being able to imagine my own past, present and future. But that perhaps is an overly ordinary way of describing it. There is something irresistibly touching about his poems, that tugs on the reader, tugs one out of the regular sequences of time. Maybe that is what all poetry does. Maybe that is what prayer does, too. Di Cicco is someone who sincerely practises both, and in that practice, his voice takes on a certain transparency that lets you walk right in.

The day is ending. I ask,

Has your life changed by becoming a priest? Where is this path taking you?

Iím not on any path. Iím just going back to what I was, the origins. Everythingís a journey these days. When you think about things in terms of journeys too much, you lose sight of the fact that you may have arrived. Itís so popular to say journey journey journey, and so unpopular to say arrive arrive arrive, that even if youíve arrived, youíre afraid to say so or even admit it to yourself. Every poem is an arrival. I can say itís part of many poems, which are an ongoing journey. Well, whatís the point of that?

My point is not to have an overview of many points of arrival; my point is to be lost in arrivals as they happen, because the back doors Ė each one has a trap door that leads into the timeless. Not back into narratives of Newtonian time. Journeys are about narrative, narrative is about Newtonian time, the timeless is what we want what we are where we live for the most part. Where we are from. Itís not where we are going, the timeless is not where we are going; timeless is what we flip into at any given time, when you stop the mental strategies of narrative.

The phone rings. Di Cicco has to get ready to give mass, at his church in the city. Sarah is fiddling with a piece of plastic on the table, and I say, Sarah, thatís his priest collar. We giggle and wait for him to get off the phone.

I donít know if I can ask him this next question or not. Itís been on my mind all day. Are you sad? Itís a simple enough question. And I donít know whether or not to tell him I have spent hours reading his poems and crying. Literally, tears run down my face. It sounds a little crazy. I havenít quite figured out what the crying is all about.

Anyway, all I can force out is,

This just might be meÖ but I find a lot of your poetry quite sad. So, uh, are you sad?

Am I sad? (long pause) The sadness, is, uh Ö is the frustration. Some people are very appetitive, and are always asking that the bar be raised before it is raised. Iím always asking that the bar be raised before it is raised. And the sadness comes out of that. Sadness is the result of not knowing what we want to know, when we want to know it. I am very appetitive about the rendering present of God, and God rendering the Divine present. And when I am frustrated by it, I get impatient. I can rest, but I am also restless. So the sadness comes out of restlessness. Wanting things that I am not supposed to want.

From God or from the world?

From God, Iíd say. What does the world have to offer? Not much, as far as I can tell. Maybe other God searchers like youÖ

Click

Sarah explains,

Thereís more light coming in, thatís all.

|