|

|

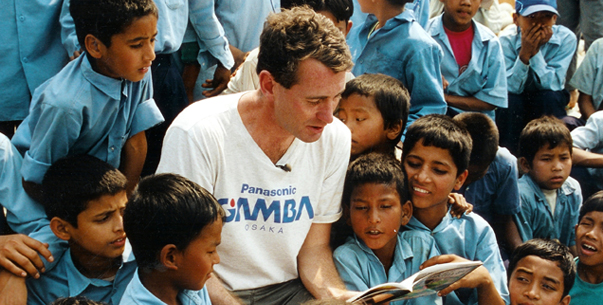

reading room

on the frontlines of social change, the strongest weapon is the written word: a profile of John Wood & Room to Read

by sikeena karmali

photo courtesy www.roomtoread.org

One of the most influential people in my life was my teacher Mirza Yusuf Ali Baig. At Park Street Collegiate High School in Orillia, Ontario, there were two teachers of colour, Mirza “Uncle,” as he later became known to me, and Mr. Harrison. My teacher, Mirza Uncle, became my self-appointed godfather and changed my life. He took the broken, disoriented, misshapen child-refugee that I was, and assembled me into a girl who stood tall, who did not accept an answer until she had confirmed it with her own process of reasoning.

Changing a person’s life is no small feat; I myself have tried in many small ways to do the same thing. It requires not only the positive faith and affirmation that this is in fact possible, but also personal commitment and the effective, innovative and sustained channeling of resources, energy and time. If you can change a person’s life, you can change the world. That is exactly what John Wood is doing: changing the world through education.

John Wood

I think that a student must have humility and be willing, indeed eager, to listen. I can’t remember who came up with the quote “I never learned anything while talking,” but to me that aptly describes the student/teacher relationship. – JW

I met John Wood last fall at a fundraising event for his NGO, Room to Read, held at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The encounter lasted a maximum of five minutes. However, he left an indelible impression, surprising me out of my preconceived notion of what he would be like.

After twelve years of global experience working in international development, specifically within the scope of education, I have encountered the full gamut of “personality” possibilities from Kofi Annan to Irene Khan to Taliban commanders. I am rarely wrong about people embroiled in the often chaotic, cathartic, jet-set business of bettering the world. It is a demanding environment that at almost every imaginable moment calls into question a person’s integrity, consistently challenging you to stay true to your higher self.

Few people are able to survive without the inflated sense of self-importance that actually changing the world can harvest on the ego. I can count the number of such people that I have met on one hand. John Wood is one of them. He navigates the world, a crowded room, even a conversation, like a true leader: with the understanding that leadership is a position of service, not a seat of privilege.

“[Enabling access to education and working with education] has made me a happier person,” reflects John. “Every day I am surrounded by people who wish to make the world a better place rather than being in a corporate environment where the focus is on profit more than on people.”

In 1998, John Wood, Microsoft’s director of business development for China, went on an eighteen-day trek through the Himalayas. He stopped for tea and met a headmaster from Bahundanda, Nepal, who invited him to visit his school. John found eighty kids crammed into classrooms for fifteen to twenty, and 450 children studying from cast-off Danielle Steele–type adult novels.

“Perhaps, sir, you could help us get more books?” the headmaster requested.

In 1999, John Wood flew to Nepal with 3000 books. Dinesh Prasad Shreshta, a rural aid worker in Kathmandu, said to him: “We should be more organized and do this properly.”

Room to Read

[Literacy] opens up so many worlds to people, worlds that they did not know existed. Education, once you have it, is not something that can be taken away from you. – JW

Room to Read’s mission is to provide underprivileged children with an opportunity to gain the lifelong gift of education. It was founded on the belief that education is the key to breaking the cycle of poverty and taking control of one’s own life. The organization has built over 2500 “Reading Room” libraries and over 200 schools. They have donated over 1.5 million books and sponsored 1700 girls through ten years of education with “Room to Grow” scholarships. In addition, the NGO creates computer and language labs in existing rural schools and publishes 70 new children’s books a year in local languages.

“Learning makes so many other areas of progress possible,” says John. “An educated woman passes on knowledge and a respect for education to the next generation. Educated people are more likely to be healthy, and much more likely to escape the cycle of poverty. I believe that if we really want to change the world for the children in the poorest countries, there is no better start than to bring them (a) vaccines; (b) clean water; and (c) education. The Gates Foundation is doing the first one on a big scale. The rest of us need to rally around the other two.”

Room to Read’s long-term goal is to help 10 million children gain the lifelong gift of education.

Building Communities

[We] design programs to empower co-investors. We believe in putting power in the hands of the community. We work in partnership and with equality, enabling communities to help themselves. – JW

Room to Read functions on the principle of building partnerships with communities. The organization engenders community ownership of education projects through its Challenge Grants. These grants require villages to contribute in a meaningful way, for example, through donated land, labour, materials or cash. A sense of ownership builds commitment among communities to work together to realize shared goals and to overcome resistance to change.

“I remember walking up a steep path for two hours to a rural village in Nepal. Mothers whisked past me on the mountainside with hundred-pound bags of cement on their backs. It was their way of proving that they were enthused about education and that they wanted to help contribute toward the building of a school for their children,” John reflects about one of Room to Read’s projects.

The Himalaya Primary School in Nepal – on the outskirts of Kathmandu – was built in a very poor community. They did not have a proper primary school for grades one to five, and requested assistance from Room to Read. The Room to Read Challenge Grant model requires that the community contribute some form of resources for each project. However, everyone in this village was poor, as they worked at local brick factories and earned the equivalent of one dollar a day.

To meet the Challenge Grant Model, the headmaster approached the brick factory owners and told them that just because the parents are poor and uneducated, their children should not have that same fate. He asked each factory owner to contribute bricks toward building the primary school. Six of the factory owners agreed. As a result, Room to Read had to contribute only US $7,000 of additional resources: cement, skilled labour, wood, desks and chalkboards toward the building of the Himalaya Primary School.

Education and Communities

Of the one billion illiterate people in the developing world, nearly two-thirds are women.

My grandmother was an educated woman. She educated my mother. My mother educated my older sisters. As a result, I have had very strong women in my life. Educating women is an investment. I would not have grown up with a love of books and an open mind without strong female role models. – JW

One of my most haunting memories is of touring the villages in the Karategin Valley in Tajikistan and being shown the spot in a village square where two twelve- and fourteen-year-old girls were publicly hanged to death. Their crime? Continuing to attend school after puberty.

I consider myself to be a women’s rights advocate, but I have stood witness to many women who, when faced with the choice of freedom, in a world where they have no public function without male legitimacy, and no tools with which to carve out that function, retreat into positions of subservience. I have always known, almost intrinsically, that the key to women’s emancipation is through education. You cannot take a woman out of the “protection” of confinement and throw her into a society that is determined to see her fail lest she set an example for her daughters, without equipping her with the necessary tools of survival. Education, literacy at the very least, is necessary for survival in the twenty-first century. An educated woman will make her own choices, break her own bonds and walk free.

Room to Read is particularly interested in helping women through education. “It’s important to get girls at a young age, who traditionally have not been educated. So many advantages [of educating girls], economic, decreased infant mortality, improved early child health…Effectively you’re educating the next generation… I returned to that school in Nepal, and I was sitting with four young girls. I grabbed a random book off the shelf and asked, ‘Can I read this to you?’ They replied, ‘No. We will read it to you.’ They were very young and had memorized the book. But they were shouting with excitement. They were so proud of their ability to read.”

Today, by the most poetic of coincidences, I myself am a teacher. I spend two hours every day tutoring a young Sikh girl who is of the same age I was when I met my teacher. I do not know who I would have become today, if all those many years ago when I came to Canada as a broken child, I had not found teachers who gave me the gift of learning.

Education ultimately became my passport to independence, enabling me to walk my own path, to carve out my own identity in a culture where women inherit the prescripted lives of their mothers, and their grandmothers before them. I too have become a self-appointed guardian, aspiring to inspire my young student until she can look around and grasp the world unfolding before her as a garden of opportunity.

Optimistic Outlook

Given the current state of the world, it would be too easy to be depressed. But I am doing something concrete, to alleviate the poverty and suffering…that is an incredible payback. – JW

John believes that world change starts with educated children. He left an executive job and millions of dollars to trek to rural villages and build schools and libraries for underprivileged children. Room to Read operates with an overhead cost of less than 10 percent compared to most NGOs, which average about 30 percent. He worked for free for the first four years, and watched his savings dwindle every month. How does that feel?

“I am optimistic,” he replies. “I am always thinking, how can we expand? Before, I used to travel as a tourist and now I travel more as a problem-solver. Yes, the scope, the need and the changes are daunting…but you cannot allow yourself to get too caught up in that. Too many people are paralyzed by the scope of how much needs to happen. You simply have to put your head down, and work.”

Room to Read hosts Treks for Literacy that give their donors an insider’s view of what few tourists ever see while participating in hands-on educational projects. Room to Read also has volunteer chapters in many North American cities. You can learn more by visiting their website: www.roomtoread.org.

Sikeena Karmali was born in Nairobi, Kenya to parents of Gujarati descent. She worked in international development and human rights from 1994 to 2004. Her first novel, A House by the Sea, was published by Véhicule Press. She lives in Vancouver and acts as contributing editor to ascent while working on her second novel.

|