|

|

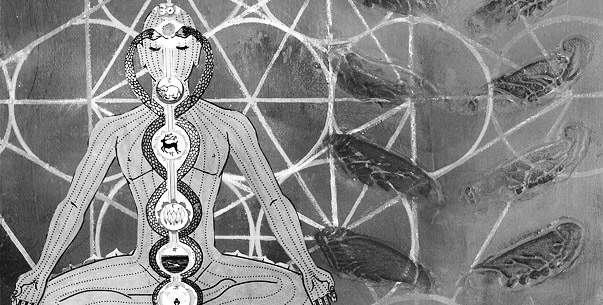

embodying transcendence

In this meditation on beauty, Vanessa Fisher finds the peace of true presence through the interplay of Siva and Shakti.

painting by claudia nicoletti

I was twenty-two when I decided to leave behind my life in the city to spend four months in the relative seclusion of a yoga ashram in the mountains. I had been attending university for the previous two years, focusing on gender and sexuality studies, with a particular interest in the historical movements associated with women’s relationship to beauty. My own interest in beauty had evolved out of a struggle with eating disorders and fluctuating acne-rosacea which had been, at times, devastating to my self-esteem. Other people often reminded me of my thin body type and long dark hair – signifiers for “beauty” within our culture. But the more my face and body constantly shifted and changed, the more typical and static definitions of beauty became increasingly unfulfilling for me.

I was soon reading everything I could find on the subject of beauty and writing as much as I could – perhaps hoping that I could heal my own difficult relationship to beauty. I was deeply interested in how women related to and understood their own beauty and how that relationship had changed with the rise of feminist consciousness. But the more my intellectual insight deepened, the more my body began to feel like a painful prison. The polarization of my body and mind acted as a symptom of my own unresolved relationship with beauty, and I found my inner battle calling out to me with a growing sense of urgency.

When I arrived at the ashram, I was assigned to lodge in the dorm named Siva – a reference to one of the most powerful gods in the Hindu trinity. Siva is often depicted with a closed third eye representing his clairvoyant consciousness through which he perceives the entire world of manifestation as a dream within his own mind. Siva ruthlessly dismantles obscurations on the path to enlightenment, offering the devotee’s heart back up to the vast landscape of his or her own eternal, pure and untouched awareness.

As I learned more of Siva, I became fascinated with the possibilities of this type of masculine self-composure. I was deeply interested in how this notion of “repossessed awareness” could offer new insight for women and the feminist movement at large. One of my favorite feminist philosophers, Luce Irigaray, advocates the need for a woman to “unveil herself for herself” as a way for her to finally repossess her own body and gestures.

When, in the last month of my stay at the ashram, I moved to the Saraswati dorm – a reference to the goddess of healing arts and musical, poetic inspiration – the relocation felt like an outward symbol for my important inward movement toward balance. I soon became interested in the stories behind Sakti, the feminine aspect of consciousness.

Sakti as the goddess becomes equated with the entire universe and, because Sakti is so diverse in her manifestations as energy, she also seemed to me much more difficult to pin down in singular definitions.

I knew that my existence as a woman would continue to be marked with the fluctuations of a self-critical mind and the painful constraints of an often superficial culture, but I also knew that my taste of Sakti’s power had left me unable to look at myself in the same way again.

Vanessa Fisher is currently an undergrad arts student at UBC in Vancouver, where she is developing her ideas on beauty, gender and women’s spirituality.

|