Technologies of Intuition

edited by Jennifer Fisher

YYZBooks / MAWA 2006

“Intuition is always contradictory and paradoxical, entailing the simultaneity of faith and suspicion, openness and skepticism,” writes editor Jennifer Fisher in her introduction to Technologies of Intuition, a collection of essays on the role of intuition in art practice. The book is published by YYZBooks, a Toronto press devoted to printing critical essays on Canadian art, in conjunction with Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA). The artists featured are all women using some aspect of the intuitive, the supernatural or the spiritual as their artistic medium. From spiritualists of the 19th century to women of the 1960s who “haunt” the discourse of art history to psychic artists of today, the book strives to enhance our understanding of artwork that is informed by “the flash of insight.”

In her effort to assert the spiritual potential underlying the creation of art, Jennifer Fisher is courageous. While many artists would describe a sublime or irrational aspect to their artistic process, the overt use of spiritual themes is often marginalized in the art world and labeled as new age, flaky or dismissible. What Fisher proposes here is that intuition and spirituality can be explored rigorously as a foundation for art practice, not placed on the sidelines.

An interesting and paradoxical aspect of the book is its use of academic language (it is a book of critical theory, after all), as the artists in the book attempt to position their intuitive processes within the language of critical discourse. While I admire this effort and understand that it is part of the agenda of the book, this sort of formalized language often obscures the intuitive spirit of the art itself. I found myself longing for more experiential presentations of the work and less academic art-speak. Of course, there are inherent limitations in using language to express the intuitive process, which is ultimately why these artists have turned to visual, somatic and psychic explorations.

The strongest pieces in the book are on Chrysanne Stathacos’ aura photography, Marina Abramovic’s epic performances and Linda Montano’s living art practice. Some of the artists/essayists, including Barbara Balfour and Karen Finley, are successful in merging art dialogue with the spirit of the subject matter – the form and content of their contributions is inherently intuitive.

If you are up for some art theory and want to go into uncharted territory, Technologies of Intuition is a fascinating record of the contradictions and paradoxes found in the intersections between language, art, feminism, spirituality and the self.

–Clea McDougall

back to top

The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom

by Jonathan Haidt

Basic Books 2006

Happiness, it seems, is more in what we avoid than what we seek. In this wonderful book, Jonathan Haidt tells us how our popular pursuit of happiness needs to be challenged, showing that it isn’t as hard (or as expensive) as we are inclined to believe, but it does require plotting a new course.

Haidt builds his story on ten Great Ideas drawn from classical thought, East and West – from the Upanishads to the teachings of the Buddha, from the Old and New Testaments to Greek and Roman philosophers. He questions each in light of what is now known from scientific research. For him, it isn’t a matter of belief in what someone else is telling us, as much as a matter of knowing what can transform our lives. Haidt’s well-researched book shows that we know a lot more about happiness than we are applying.

The book starts with an exploration of how our minds work, and this is not how we might suppose; we are of two minds, and they often conflict. “Like a rider on the back of an elephant, the conscious, reasoning part of the mind has only limited control of what the elephant does.” Haidt says that we have to start by finding ways to have the “rider” and the “elephant” work better as a team – a metaphor that the author uses with brilliance throughout the first section of the book.

Refreshingly, The Happiness Hypothesis does what it claims in showing us how seemingly simple things such as the Golden Rule and understanding our own in-built hypocrisy (the “rose-coloured mirror” problem) lead us within, where we can re-examine our tendency to try to make the world conform to our desires.

Haidt’s use of current psychological research challenges the stoic idea that we ought to break our emotional attachments to people and events, which opens up new ways to look at where love comes from and what “true” love might be. But he goes even further, giving us important insights on why we so often grow from adversity and why “freedom can be hazardous to your health.” He shows how virtue and morality can be developed and strengthened by going back to the more expansive ideas of the ancients.

In a clear and non-dogmatic way, he takes us into his own research on the “sacredness, holiness, or ineffable goodness in others and in nature.” It is insightful and inspired, all the more so coming from someone who otherwise claims to be an atheist.

Find your way to connect with this book – don’t just read it. As Haidt says, words of wisdom about the meaning of life wash over us every day but they do little unless we savour them, engage with them, question them, improve them and connect them with our lives.

–Swami Sivananda

back to top

Writing Begins with the Breath: Embodying Your Authentic Voice

by Laraine Herring

Shambhala Publications 2007

There is something very attractive in the notion that, through writing, we can reveal ourselves, express our humanity and even heal ourselves, and there are almost as many books on the market about the writing process as there are people who want to be writers. But do we write to become better people? Does self-improvement, in turn, make us better writers?

These are the questions I asked myself as I read Laraine Herring’s Writing Begins with the Breath, a book that combines advice on writing with yoga “Body Breaks,” as well as Buddhist philosophy and practices. As a practitioner of all three, I was very curious about how my existing spiritual pursuits could serve to make me a better, or at least more grounded, writer.

The book, which is divided into three sections, is chockfull of wise observations and advice. The first section encourages the writer to explore his or her relationship to the act of writing itself; the second looks at some of the more concrete and practical issues in the writing process (such as setting, voice, characterization and discipline); and the final section explores themes related to the completion of writing, including post-project blues, the necessity of letting go of the work and the need to surrender the self in order to allow writing to emerge beyond the constraints of the writer’s ego.

Each chapter ends with a series of suggested exercises meant to trigger free-writing and self-exploration, and some of these prompts are excellent. Writers in any stage of their process would do well to ask themselves what fear, risk or change means to them, to look at what would be lost if they stopped writing and to determine what their obstacles are on the creative path. Some of the less concrete prompts miss the mark: How exactly does one “wine and dine” one’s writing? And how does writing the story of the relationship to a particular tree teach about setting?

Writing Begins with the Breath is an encouraging, friendly book that does not shy away from the difficulties of the writing process, and offers solutions to blocks of body, mind and spirit. There is much to be learned about all three here, but as a reader and a writer I felt a split focus, with more emphasis on self-improvement than on the development of the work itself. Knowing and grounding ourselves might indeed make us better people, but the best writing not only takes us out of ourselves, it is often far wiser than we will ever be.

– Tess Fragoulis

back to top

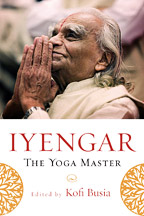

Iyengar: The Yoga MasterIyengar: The Yoga Master

edited by Kofi Busia

Shambhala Publications 2007

To many in the West, the name B.K.S. Iyengar has been synonymous with the study and practice of yoga since the mid-1960s. As a result of violinist Sir Yehudi Menuhin “discovering” Iyengar and subsequently introducing him to the West, most classes occurring in the world today have been informed by his method of teaching to some degree. Aspects such as proper alignment, modifications, awareness and poise all echo the methods of this master student of yoga. As a practitioner of Iyengar Yoga myself, I was very interested in reading Iyengar: The Yoga Master to find out more about a man whom I have never met, but whose teachings have influenced my life on a deep level.

Noted for his pioneering texts on yoga philosophy such as Light on Yoga, Light on Pranayama, and Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Iyengar certainly deserves to be honoured in a book like this one, which serves as a tribute to his life’s work. Published on the eve of his 90th birthday, Iyengar: The Yoga Master serves as an insightful recollection of Iyengar’s loving and exacting methods for teaching yoga to his many students and admirers. Many of the contributors to this volume are big names in the world of yoga, and each has humbly written a chapter sharing stories and insights that are a testimonial to the massive impact of Iyengar’s teaching. Notable teachers such as Shiva Rea, Baron Baptiste, T. K. V. Desikachar, John Friend, Rodney Yee and Patricia Walden all bow down at the feet of Iyengar in the form of a collective memoir.

From a historical perspective, this book allows the reader to catch a glimpse of the effect of Iyengar’s influence and how yoga has taken root in our social consciousness over the past few decades – from its humble beginnings in community centres to the multitude of large-scale international yoga conferences now happening throughout the world. The book also includes information about physiology, psychology, Sankhya philosophy, Ayurveda and yoga therapy, all of which inform Iyengar’s method of teaching.

Each chapter is sewn together seamlessly by editor Kofi Busia, starting with a short thought, philosophy or memory relating to Iyengar. Busia, who is himself a senior Iyengar teacher, has a way of letting the essence of his teacher shine through. Having not been in the presence of B. K. S. Iyengar before, I developed a deeper understanding and relationship with him by reading the abundantly warm reminiscences in this tribute.

Though it is not a manual, this book inspires correct yoga practice. As illustrated in the book, tapping into this potential can guide the reader on beginning, continuing and inspiring others to observe and apply the invaluable teachings of yoga in their life. These teachings were meant for the world, and this book sheds light on how lovingly Sri B. K. S Iyengar has devoted his life to bringing this ancient wisdom alive.

–Paul Gangadeen

back to top

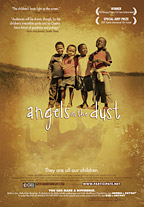

Angels in the Dust

written & directed by Louise Hogarth

Participant Productions 2007

Since I watched this film, the image of one of this documentary’s main characters has been flashing into my mind before sleep: eight-year-old Lillian laughs as loud as she pleases and has a big, wide smile. It’s hard to believe that this laughing, dancing girl is HIV-positive and a survivor of rape, like many of the other children at Boikarabelo School and Orphanage.

While Angels in the Dust is a film about the devastation of AIDS in South Africa, it’s not one that leaves you feeling hollow at the end – its focus is on having the power to do something. The film is about Boikarabelo, an inspiring AIDS-orphan village just north of Johannesburg. Over the period of three years, filmmaker Louise Hogarth gained the trust of the village and began documenting the work of Marion Cloete and her family, who left their comfortable upper-middle-class life in Johannesburg 19 years ago to build a school and community for children being orphaned by HIV and AIDS in the region.

Marion Cloete is a professional therapist and long-time activist who cares for the children and helps them work through traumatic experiences in their pasts such as incest, rape, child prostitution and parental abandonment. The camera even goes into the group therapy room where the children gather up their feelings and scream into pillows about all the things they’ve seen and lost. Marion facilitates and her two daughters are nearby in case the kids need support.

Despite all of the complicated emotions surrounding the care of the children and what they’ve been through, the Cloetes help the children to work toward forgiveness and to keep in touch with the surrounding community, knowing they can’t recreate the sense of belonging that relatives and neighbours bring to the children’s lives. The Cloete family keeps in touch with surviving parents, asking permission before making any care decisions for the children, and they treat people with dignity – even a man who continues to sleep around without protection, despite knowing that he has AIDS and that he has already killed a half-dozen women in the area this way. His crimes notwithstanding, Marion Cloete and her husband visit him on care-rounds and advocate for him to get medical treatment at a nearby hospital.

The empathy and humanity of the Cloetes has deeply inspired me. I was happy to find out that the film is part of a longer-term project to financially support the Boikarabelo project and ensure its work goes on. The film’s distributor, Participant Productions, is building a social action campaign alongside the launch of the documentary, partnering with the AIDS Healthcare Foundation to raise awareness about the social and healthcare related issues surrounding HIV and AIDS. They’ve also constructed a “virtual orphanage” on their website that allows viewers to take a tour of Boikarabelo and find out more about day-to-day life in the community.

To find out more about the film or the Boikarabelo project, please go to: www.participate.net/angels

–Luna Allison

back to top

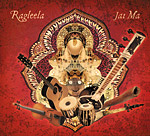

Jai Ma

by Ragleela

Omkar 2007

Listening to Jai Ma stirred a memory of the first time I saw Ragleela’s sitar virtuoso, Uwe Neumann, accompanied by the superb percussion of Shankar Das at the annual Om festival near Bancroft, Ontario in 1999. I was intrigued not only by the duo’s skills in mastering classical Indian sounds, but also by the yogic spirit that emanated from their music.

Departing from the traditional ragas that these two musicians know so well, Neumann and Shankar Das gathered a group of friends with astounding harmonic and rhythmic abilities to create Jai Ma – a fusion of Indian melodies with Western and Middle Eastern beats. Jai Ma is one of those rare albums during which I never skip a track because each seems to flow perfectly from one to the next, whether I’m relaxing in my hammock, driving home from work or washing the dishes.

The opening track, “Over the Mountain,” gives the listener a taste of the unique musical journey that is to follow in the next hour – it begins slowly with the lone sitar, gradually accompanied by complex guitar patterns, intricate violin lines and rapid grooving beats of Indian tablas and other percussion. When listening to the spiritually charged musical conversations in inspiring tracks such as “Nightwalk” and “Return of the Prophet,” a particular mood is evoked for contemplating the vicissitudes of life. The didgeridoo interlaced with complex configurations of guitar, clarinet and percussion in “Caravanserai” transports us to a rhythmic desert-like journey, while reverberating textures of “Sansonica” stimulate the listener to marvel upon the awesome power of sound.

I was particularly touched by “Silencium,” which is a silent dedication to Neumann’s mother, as well as his teacher and a close friend, all of whom recently passed away. The track, which appears near the end of the disc, creates a sense of spaciousness and an emptiness that reflects the subtle tranquility between each note played on the album. Ragleela’s journey concludes with the meditative notes of a sansa; the minimalist nature of the finger-instrument reminds the listener to remove the dust from the mirror of the heart and enjoy its music as a beautiful reflection on simplicity.

From the soothing melodies of “View of the Green Mountain” to the joyful, jazzy ragtime raga of “Camp in Town,” this album presents both a graceful fusion of our era’s diverse musical spheres and a reminder of the vast potential for unity in the face of the plurality that each of us contains within ourselves.

After listening to Jai Ma, it is clear to me that the album is Ragleela’s devotional expression to the Divine Mother. The disc is both a beautiful prayer dedicated to finding ultimate truth and a message of love, friendship and happiness. Its richly textured, beautiful melodies and beatific sounds nourish the spirit, and the fresh, improvisatory quality results in a sacred musical jewel not to be missed.

–Kory Goldberg

back to top

Healing the Divide:A Concert for Peace & Reconciliation

various artists

Anti 2007

There is something about the plight of the Tibetan people that has always resonated with me, as with many people in the Western world. Certainly, there’s a striking contrast between the pragmatic, materialist and militaristic Chinese conquerors of Tibet, and the essentially spiritual Tibetan government-in-exile. In the words of the Dalai Lama, who introduces Healing the Divide, the culture of Tibet is one that “specifically focuses on the internal development of human thought, emotions and mental states.”

The divide between pragmatic materialism and the inner world is one that artists must constantly confront as well, and perhaps this helps explain the extraordinary range of talent that gathered in the Lincoln Center on September 21, 2003 for this concert to benefit Tibetan Buddhists in exile.

Beginning with a powerful invocation by the Gyuto Tantric Choir, purveyors of a 500-year-old Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the CD offers a flow of indigenous and modern Indian, American, African and Tibetan musical energies that effortlessly cross national, cultural and spiritual divides. This is best exemplified by the two duos featured on the disc. The sensitive collaboration between Nawang Kechog, a Tibetan avant-garde musician, poet and sage, and R. Carlos Nakai, a Navajo / Ute flautist, incorporates Native and Tibetan prayers for peace as well as virtuoso musical performances. A similar balance of austerity and soulfulness is struck in Philip Glass’s performance with Gambian kora player Foday Musa Suso. Anoushka Shankar offers a spacious and spirited sitar raga on this recording, while Tom Waits brings the concert to a close with his ever-present sly humour.

Waits comes to the Tibetan Buddhist fold via The Beats and Jack Kerouac’s particular brand of dharmic musing, and The Kronos Quartet brings an understated, loosely arranged stringed accompaniment to his rants and shantys, each of which seems chosen to resonate with the theme of the concert. This is especially the case for the last number on the CD, “Diamond in Your Mind” – a composition previously unrecorded by Waits.

After listening to the concert a few times, both at home and while working, I’ve found that it creates a calming, meditative focus. There are interesting and unexpected resonances to be found – for instance, between the timbre of the chanting Tibetan monks and Waits’ growling vocals. The overall eclecticism of this disc speaks optimistically to an audience that is open to a broad range of rich musical cultures – really the antithesis of “narrowcasting.”

This CD was conceived as a fundraising tool for Richard Gere’s nonprofit organization Healing the Divide, and each sale of A Concert for Peace and Reconciliation pays for a year of healthcare for an aging Tibetan Buddhist monk or nun living in exile in Dharamsala. For more information on this project, please go to: www.healingthedivide.org.

–Vincent Tinguely

back to top